I was planning to spend my weekend editing The Business of Freelance Comic Book Publishing now that the Kickstarter campaign is fully funded, but I received quite a few requests to opine on the Fables situation, so I’m taking a break from page formatting to give my opinion on this issue.

I’m not going to address the moral or ethical position of either party or the broader attempts to alter copyright law. I’m not going to get into the reasons why Willingham is trying to do what he’s doing or whether or not it is justified based on the way he may or may not have been treated, because I don’t know what happened.

I will try to explain what is going on from a legal perspective, based on my experience as a comic book attorney, and offer some insight on how this could impact the wider industry in the future.

I’m going to structure this in the same way I organize lessons for the Comics Connection community. First, I’ll describe the scenario to get everyone on the same page. Then I’ll explain the underlying legal concepts involved. After that, we can discuss the business realities of what’s happening and wrap up with some things for you to think about.

Obviously, this is an opinion piece. It isn’t legal advice and I’m not claiming this is the final word on the issue, so please read it in that context.

How Did We Get Here?

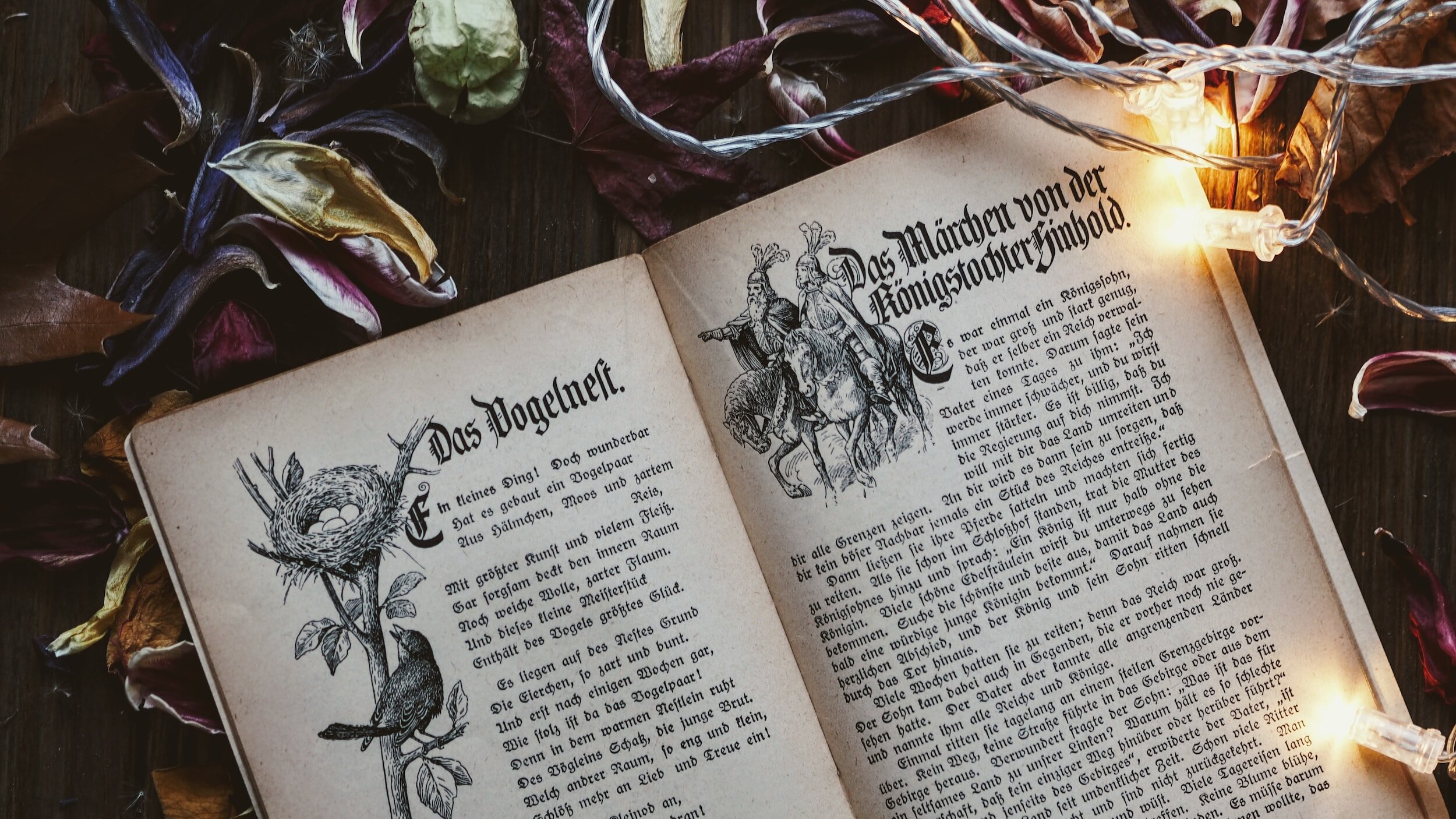

Our story starts back in the 16th century when the Brothers Grimm collected folklore and stories from across Europe including Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, and Sleeping Beauty. These stories have become famous in the Western World over the centuries and interpreted in a variety of media including, books, films, and comics, including Fables.

In July 2002, DC published Fables under its largely creator-owned Vertigo imprint, with Bill Willingham as the writer. Since then, there have been 115 registered copyrights for different issues of Fables, some showing Willingham owning the text and DC owning the art, some showing a transfer by written agreement apparently from Willingham to DC. There have also been several media projects spun out of Fables, including multiple video games

Last week, Willingham published a statement on his Substack, indicating his intention to place Fables into the public domain.

“As of now, 15 September 2023, the comic book property called Fables, including all related Fables spin-offs and characters, is now in the public domain. What was once wholly owned by Bill Willingham is now owned by everyone, for all time.”

Less than 24 hours later DC responded with a strong rebuttal:

“The Fables comic books and graphic novels published by DC, and the storylines, characters, and elements therein, are owned by DC and protected under the copyright laws of the United States and throughout the world in accordance with applicable law, and are not in the public domain.”

Publishers of various types and sizes also weighed in largely in support of DC’s position.

The professional comic book community reacted with positive and negative comments, but most people were just confused.

In an attempt to alleviate the confusion, we need to explore several questions:

What is Copyright?

What is Public Domain?

What is a Creator-Owned deal?

What are the Unknown Factors in this Scenario?

What are the Implications for the Creator-Owned Comic Book Industry?

What is Copyright?

Before we can talk about whether or not Willingham can put the Fables copyright into the public domain, we need to understand what copyright and public domain are.

Copyright is the intellectual property right protected by federal law “for original works of authorship in any tangible medium of expression”. In its most basic form, a copyright gives the owner the right to make a copy (hence the name), but it also governs who can use or exploit the work for any type of gain, like making comics or films from a story.

Whoever controls the copyright to a particular story decides how that intellectual property (IP) is used and who gets paid for it. Keep in mind I didn’t say whoever creates a particular piece of IP. In many cases, the creator is not the ultimate owner, and it is very easy for a creator to give away control over the IP they create if they don’t understand their legal and business relationships concerning their creations.

You can only sell what you own, and you cannot sell what you do not own. You can’t put it in the public domain either.

What is Public Domain?

The IP protections granted by copyright law do not last forever. “Depending on when a work is registered copyright lasts for a number of years.” The years that copyright lasts is called the copyright term. When that term ends and can no longer be renewed, the work becomes part of the “realm of materials that is unprotected by intellectual property rights and free for all to use and build upon.” This realm is referred to as the public domain.

Public domain is not designed to be a poison pill or a mechanism for a creator’s symbolic hara-kiri. The stated purpose of the public domain is to stimulate creativity in the present by drawing inspiration from the works of the past. The concept is that ideas come from the organic interaction between the different stimuli you are exposed to and your imagination and perspective at the time you encounter the stimulus. The public domain argument is if no one could build on the ideas of the past because they were always worried about infringement, progress would diminish because creators would have to continuously reinvent the wheel.

It should be noted that public domain works can be used to create derivative IP that is protected by copyright, trademark, and other IP rights. For example, Dracula is in the public domain, but if you decided to make a Dracula comic, you couldn’t base your book on the Boris Karloff movie, the Gary Olman version, or Voyage of the Demeter. You can only use the version in the public domain. You cannot use any copywritten version held by another person or company.

So, it is the doctrine of public domain that allows companies like Disney to create new works based on classic stories like Snow White, The Little Mermaid, Beauty, and the Beast, and many others, like the Fables creator-owned deal.

What is a Creator-Owned Deal?

The Fables situation is complicated by the fact that the book was released under what the comic book industry refers to as a creator-owned deal. Creator-owned comic book publishing is the development, production, and commercial distribution of narrative sequential art with the support or assistance of a third-party publisher. In most cases, the creator is responsible for producing and promoting the book, and the publisher is responsible for the distribution, advertising, sales, and other business functions. This kind of comic differs from independent publishers (where the creator owns the IP rights) and freelance comic creators (who normally own none of the IP they help create). The difference between a creator-owned publishing deal and a traditional publishing deal is that the comic book publisher often seeks to retain and control the film, television, and other media rights associated with the comic.

What are the Unknown Factors?

So now we know that Willingham created IP based on public domain stories, signed a creator-owned deal, and now is attempting to place the IP in the public domain against the wishes of DC.

What we don’t know is if he can do any of this.

I’ve asked other comic book attorneys who are much smarter than I am and the consensus at this stage is that unless we can review the contracts between Willingham and DC, we can only guess what’s really going on.

One attorney posted publicly on the Comic Connection Facebook page yesterday:

If you're a copyright owner, and you've assigned the rights or a portion of the rights to someone, you don't get to grab those rights and thrust them into the public domain, even if you are the author. So, as to who owns what, the contracts executed by the authors and the owners of the copyright assignments are determinative and take precedence over authorial intent to abandon copyright.

Another expert on copyright and comics said privately:

“So many contracts we've seen and discussed at our CLE give the creator authorship for copyright purposes but at the same time assign rights to the publisher on an exclusive basis. In that instance, the author would not have the right to license the rights to others. The issue gets more complicated when, as here, the writer and the publisher are registered as joint owners of the copyright, but with Willingham's rights transferred to DC and DC as the author of the art as a work made for hire. Obviously, as we all agree we'd have to see the underlying contract, but it doesn't seem likely that DC legal would approve a contract in which an author could scupper the deal by fiat.”

In short, we need to see the contracts to know for sure, and we’ll probably never see the contracts, even if this case goes to court.

What are the Implications?

Various elements of the comic book community could be impacted by this move, but not in the ways that are currently being discussed.

First, Willingham’s sentences in his initial statement contradict each other because of the way the copyrights are filed.

As of now, 15 September 2023, the comic book property called Fables, including all related Fables spin-offs and characters, is now in the public domain. What was once wholly owned by Bill Willingham is now owned by everyone, for all time.

At most, he owns the scripts, not the character designs, artwork, or any of the visual elements of Fables. He doesn’t own the original ideas, which were public domain to begin with, and he doesn’t have the right (by his admission) to place the DC published titles in the public domain. So what is left for him to abandon to the public domain beyond the script?

In addition, even if Fables was a wholly original work and there is some language in his contracts that would allow him to prevail in court, it won’t get to that point. He states in his post that he doesn’t have the money to fight a conglomerate like DC/ Warner Brothers/ Discovery in a lawsuit and without money, it is difficult to prevail in the American legal system, especially when it is an individual creator against a megacorporation.

On the other side, the statement made by DC is accurate:

“The Fables comic books and graphic novels published by DC, and the storylines, characters, and elements therein, are owned by DC and protected under the copyright laws of the United States and throughout the world in accordance with applicable law, and are not in the public domain.”

DC isn’t claiming ownership of the underlying public domain work. They are saying they own the comics they published, which Willingham acknowledged in his statement. From a legal perspective, DC is on very solid ground.

How Does This Affect You as a Comic Creator?

Beyond Bill Willingham, any other comic book creators considering creating Fables comics based on Willingham’s statement should stop considering that for three reasons. First, it is unclear whether the public domain transfer is valid. Second, even if it is valid, the ROI on your Fables related comic probably does not justify the headache of getting a cease-and-desist letter from DC. Finally, Fables itself is based on public domain work. If you want to make a comic based on fairy tales, go for it. Just don’t use anything that’s part of this copyright.

There is a wider consideration for other comic creators trapped in creator-owned deals they are unhappy with. You may not be in the same situation as Willingham. Perhaps you too feel your publisher isn’t living up to their obligations relative to your rights, royalties, and responsibilities in your contract. Maybe your work isn’t based on public domain characters. Maybe your contract gives you more leverage to assign and transfer the copyright. Maybe you’re so fed up with dealing with them that you’d rather put your IP in the public domain rather than let them profit from it.

Could you have more success than Willingham is likely to have? Maybe. Maybe if a lot of creator-owned deals faced this kind of symbolic hara-kiri, it would put another nail in the coffin of the IP farms posing as comic book publishers and accelerate the consolidation we seem to be witnessing.

But before you post something on your Substack, have an attorney familiar with the comic book industry look things over and explain your options to you.

Have fun with your comic.

Gamal

Gamal Hennessy is an attorney, author, and business consultant with more than twenty years of experience in the comic book industry. He is the author of The Business of Independent Comic Book Publishing, The Business of Freelance Comic Book Publishing currently available on Kickstarter, and the co-founder of Comics Connection.